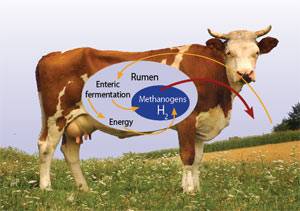

As explained in previous posts, industrial farming of cow's has become a major contributor to global GHG emissions. Cows eat A LOT! They are ruminant mammals meaning they ferment ingested food in the first of their four stomachs before passing it onto the next stomach for digestion. During the break down of plant material (enteric fermentation) hydrogen is released which is used by digestive microbes (methanogens) to produce methane which must then be removed from the cows system back through the esophagus and out of the nose and mouth by exhalation or belching.

|

| Processes of Enteric Fermentaiton Source: Singh and Sikka (2008) |

Research has been conducted since the 1960s looking at various dietary supplements that can reduce the methane producing ability of cattle (Lee and Beauchemin, 2014). One of the most effective of these has been the practice of chemically adding nitrates to cow feed. By doing this methanogens within the cows gut will produce ammonia (NH3) preferentially to methane (CH4), thus reducing the amount of methane that is released into the atmosphere. Zhou et al's (2011) in vitro study found methane production to be reduced by nearly 70% when rumen fluids were incubated with sodium nitrate (NaNO3).

Yes, 70%! In the USA this kind of reduction would be equivalent to reducing their population by 61.4 million cattle!

Unfortunately there is one very large problem with this method. If nitrates are broken down to nitrites in the rumen there can be interference with red blood cells which in a number of studies have resulted in cows dying or needing serious medical treatment. More research is therefore required before this method becomes appealing to farmers.

An alternative to directly adding nitrates to the diet is to add oils which appears to have a number of positive effects similar to those of nitrates. The most important of these is the suppression of methanogens. In a study by Mcginn et al (2004) as much as a 22% decrease in methane output was noted when ruminants were fed a diet supplemented with sunflower oil! Some oils have the added benefit of improving the productivity of the cow. Grainger et al (2008) found that increasing the oil component of the diet by 1% using whole cotton seed, caused a decrease in methane emissions by 6% while also increasing milk output! More milk from a single cow perhaps means less cows overall would be needed?

Other studies have shown similarly promising results using a variety of other oils including palm oil (uh oh!). There is certainly potential here although there are concerns over whether repeated feeding over an extended period of time would allow the rumen to adapt to a new 'feed environment' and revert back to producing just as much methane as previously.

anti-Methane Vaccine

What if we could suppress the population of methanogens in the gut? Less methanogens = less methane production. Simple!

Turns out this could be a viable option. The only hurdle is the very large number of methanogen strains that preside in the rumen and therefore an effective vaccine would need to be able to act on a range of different substrates (Wedlock et al, 2013). This makes the production of a vaccine an extremely difficult task. One study produced a vaccine that accounted for over 52% of the methanogen population in the ruminant animals they were testing and yet while methanogen population composition changed, there was no significant difference in methane output (Williams et al, 2009).

Methane inhibitors

One of the most recent and most promising anti-methanogen technologies is that of the inhibitor. Different to vaccines in that they do not reduce the population of methanogens, these inhibitors have been shown to vastly reduce the capability of them to produce methane. An investigation into adding 3-nitrooxypropanol (3NOP) to animal feed has produced results showing 30% decreases in methane output while, importantly, having no negative effects on the cows growth or milk production. In fact those cows treated with the inhibitor saw increased weight gain and it is hypthesised that this is due to less energy being used in enteric fermentation and instead being used for tissue synthesis (Hristov et al, 2015).

A win win for farmers!?

|

| Cows fitted with devices to measure the composition of exhaled gases. Source: National Geographic |

But is it enough? Final thoughts...

To me 30% doesn't seem like a 'climate-change-solving' reduction. It certainly is difficult to see 30% as a success when simply having 1 less burger a week could potentially have the same impact. It's all a step in the right direction but surely we need more than 30%!

I get the feeling I have only scratched the surface here. The vast amount of literature on this subject provides scope for an array of new technologies which can decrease bovine emission. All the methods here involve preventing the production of methane, what of the methods that can capture and utilise this methane post-production? Check back in the next few weeks to find out!

I really like your research on the technological side of animal farming and ways involved that could reduce methane emission, hence reducing the impact on climate change. However, I am wondering what is your thought on the carbon emission within the life cycle of meat production (i.e. fossil fuel burnt for producing feeds, fertilisers, antibiotics and for machinery as well as transport) as they could potentially outweigh the power of methane warming up the climate.

ReplyDeleteI am also doing my blog post on related topics. It would be nice to see things from a different perspective.

Yes I certainly think this is a major problem, in fact I was reading a Nature article recently about a study conducted by Vermeulen (2012) (http://www.nature.com/news/one-third-of-our-greenhouse-gas-emissions-come-from-agriculture-1.11708) which suggested that carbon dioxide actually makes up 86% of all greenhouse gas emissions from the food system and, as you say, methane emissions are perhaps not as significant!

DeleteLuckily there is a lot of work to suggest that intensive farming can actually increase carbon sequestration while there is promise of a lower reliance on fossil fuels as we move more and more towards renewable energy.